Paul Thek

Untitled (The Cross of Pollyanna), 1975/92

Edition 20 of 25

Etching on handmade Twinrocker paper

10 x 7.75 in (25.4 x 19.7 cm)

13.25 x 10.75 in (33.7 x 27.3 cm) Framed

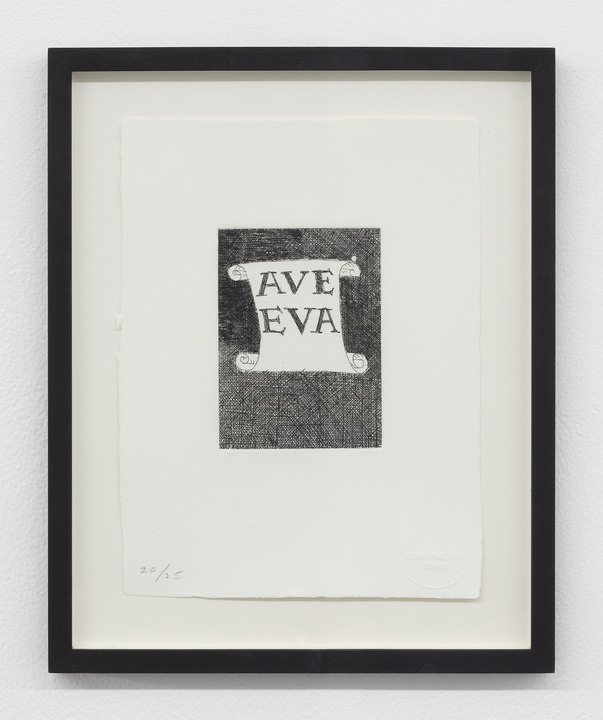

Paul Thek

Untitled (Ave Eva), 1975/92

Edition 20 of 25

Etching on handmade Twinrocker paper

10 x 7.75 in (25.4 x 19.7 cm)

13.25 x 10.75 in (33.7 x 27.3 cm) Framed

Paul Thek

Untitled (Horned Cross), 1975/92

Edition 20 of 25

Etching on handmade Twinrocker paper

10 x 7.75 in (25.4 x 19.7 cm)

13.25 x 10.75 in (33.7 x 27.3 cm) Framed

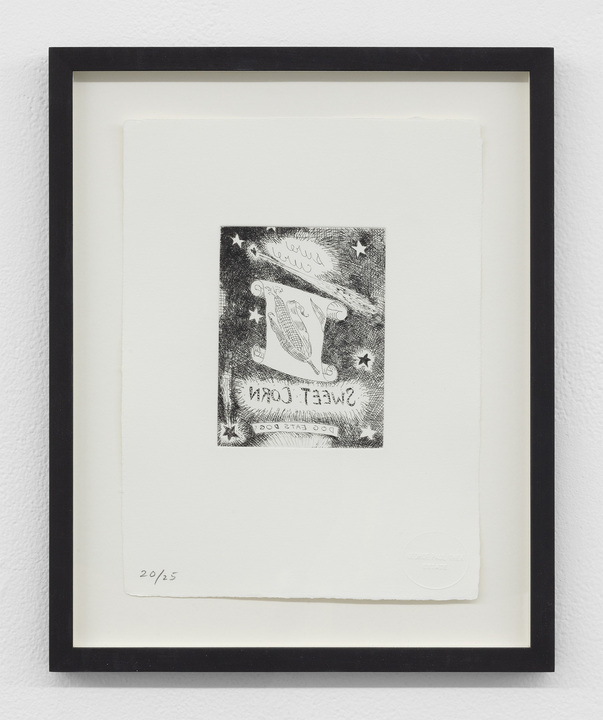

Paul Thek

Untitled (Sweet Corn), 1975/92

Edition 20 of 25

Etching on handmade Twinrocker paper

10 x 7.75 in (25.4 x 19.7 cm)

13.25 x 10.75 in (33.7 x 27.3 cm) Framed

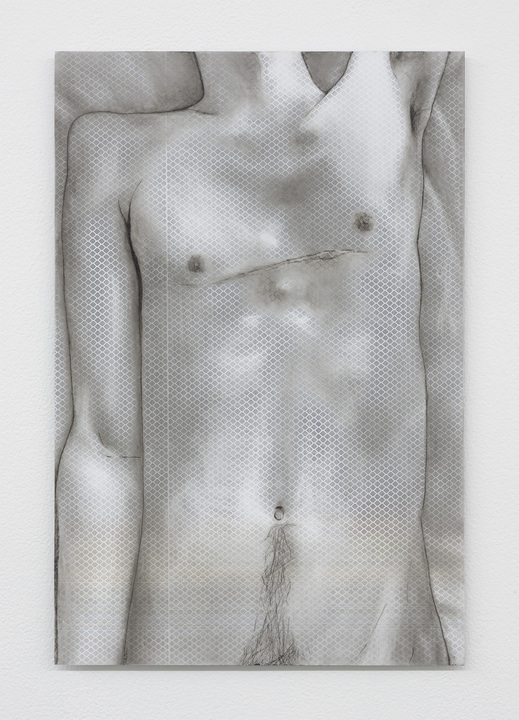

B. Ingrid Olson

Cuirass, 2020-2021

Inkjet print and UV printed matboard in aluminum frame

20 x 14 in (50.8 x 35.6 cm)

Sam Lipp

Headless (Acéphale), 2021

Oil and prismatic film on steel

18 x 12 in (45.7 x 30.5 cm)

Covey Gong

Untitled, 2021

Bronze, brass, aluminum, polyester

30 x 20 x 31 in (76.2 x 50.8 x 78.7 cm)

Sam Lipp

Headless (Acéphale), 2021

Oil and pencil on steel box

11.5 x 11.5 x 9 in (29.2 x 29.2 x 22.9 cm)

Covey Gong

Untitled, 2021

Brass, polyester, cotton, nickel

11 x 6.5 x 2.25 in (27.9 x 16.5 x 5.7 cm)

Sam Lipp

Untitled, 2021

Oil and prismatic film on steel

18 x 12 in (45.7 x 30.5 cm)

This Is My Bodys is an exhibition featuring work by Covey Gong, Sam Lipp, B. Ingrid Olson, and Paul Thek.

The title for the exhibition comes from text within an etching made by Paul Thek in 1975, whose companions from the same series are included in this exhibition. Only a portion of these etchings were proofed in the artist’s lifetime, many were unprinted, and the series was not known in its entirety until 1989, a year after Thek’s death, when 28 etched copper plates were discovered in the artist’s personal storage unit amongst a multitude of other works. The entire series of etchings involves a poetic play on punctuation and mirroring, the first plates etched by Thek without realizing the fact that the etched copper plates would print their contents in reverse. Thus THE CROSS OF POLLYANNA and SWEET CORN read from right to left while subsequent plates, like AVE EVA, incorporate the mirroring into the work itself.

The body and mirroring appear as motifs elsewhere in this exhibition, perhaps most clearly in the work of B. Ingrid Olson. Her work Curiass refers to the breastplate/backplate of a suit of armor and is composed of one image framed within another. The exterior image pictures an assemblage of folded cardboard and brown packing tape topped by a ceramic, ovular, breast-like prop. The inner image is the reflective interior of a soft tube pressed against a breast, forming a channel between camera lens and nipple. The mirror-like interior of the conical shape both abstracts and camouflages the breast, repeating and radially extending the darker tone of the areola in the rippled reflection. As a result, the interior image feels like an x-ray through an armor made of detritus.

The body in relation to boundaries and space leads directly to Sam Lipp’s three painted works in the exhibition. The two works on view in the main gallery depict bodies whose heads are cropped by the boundaries of their surfaces. Both works share the same title: Headless (Acéphale), a reference to Georges Bataille’s public review whose 1936 first issue’s cover depicted a headless version of Leonardo’s embodiment of classical reason, Vitruvian Man. The first of Lipp’s headless figures is painted on a medical waste disposal box and, although the entire surface is covered in Lipp’s unique brand of painterly interference, the words “BioReference” and “GenPath’’ remain clear and legible. Each of Lipp’s other works are painted on prismatic film mounted to steel, a surface which recalls the hard and smooth reflectivity of a street sign, however in this context creates a visual interference in the figurative paintings that, when viewed at an angle, adds prismatic rainbows to otherwise monochromatic images.

On the far wall in the rear of the main gallery, a violet crushed velvet fabric hangs from ceiling to floor. Inset in the center of the fabric is an ink drawing hovering somewhere between abstraction and figuration. Covey Gong’s three untitled works resist categorization; the metal and knit polyester floor sculpture exists somewhere between creature and architecture, its four thin legs enabling an oscillation between porcupine and scale model geodesic dome. The qualities in Gong’s work remind us of the experiential pleasures of looking and of being a body in space, sentiments expressed by Susan Sontag in her influential essay Against Interpretation. According to Sontag’s biographer, the title for the essay was inspired by a conversation with her close friend, Paul Thek. One day, when Sontag was “talking about art in a cerebral way that many complained was a bore,” Thek interrupted: “Susan, stop, stop. I’m against interpretation. We don’t look at art when we interpret it. That’s not the way to look at art.”

Covey Gong (b.1994, Hunan, China) received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and currently lives and works in New York. Recent solo exhibitions include And Now, Dallas (2019); Bodega, New York; and Salt Projects, Beijing. Group exhibitions include Unclebrother, Hancock, NY; Museum Gallery, Brooklyn; Mother Culture, Los Angeles; And Now, Dallas; Giovanni’s, Queens; and 48/19 Liebhartgasse, Vienna.

Sam Lipp (b. 1989, London) lives and works in New York, NY. Select solo exhibitions include Bonny Poon, Paris (2019); Bodega, New York (2016 & 2014); and Central Fine, Miami (2015). Recent group exhibitions include Cell Project Space, London (2019); Grand Palais, Paris (2019); Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn (2019); National Portrait Gallery, London (2018); Espoo Museum of Modern Art, Espoo, Finland (2018); Kate Werble, New York (2017); and Night Gallery, Los Angeles (2016). He will have his third solo exhibition with Bodega in 2022.

B. Ingrid Olson (b. 1987) lives and works in Chicago, Illinois. In 2022, Olson will have concurrent solo exhibitions, History Mother and Little Sister, at the Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts at Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. Recent solo and two-person exhibitions include i8 Gallery, Reykjavík (2019); Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo (2018); and The Renaissance Society, Chicago, (2017). Select group exhibitions include Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, Los Angeles, (2021); The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, (2021); The Museum of Modern Art, New York (2018); and Aspen Art Museum, Aspen, (2018).

Paul Thek (b. 1933, Brooklyn, d. 1988, New York) studied at the Art Students League and Pratt Institute in the early 1950s. One of the foremost artists of the postwar era, his unique place in art history may perhaps even be compared to that of Joseph Beuys. Like Beuys, Thek extended the concept of the artwork and broadened perceptions of art and life. A deep sense of religion and the belief that art should serve society were a source of both inspiration and strength. In the mid-1960s, Thek produced a well-known body of work, The Technological Reliquaries, wax sculptures that looked like raw meat or human limbs were encased in plexiglass vitrines. In the late 1960s and 1970s, Thek’s room-sized installations were exhibited at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam; the Moderna Museet, Stockholm; “Documenta V,” Kassel; and the Kunstmuseum Lucerne. Thek’s work is included in numerous American and European museum collections with a particularly strong representation of his drawings at the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. From 2010 through 2011, Diver, a retrospective of Thek’s work curated by Elisabeth Sussman and Lynn Zelevansky traveled from the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York to the Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, and the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles. An exhibition of major works from Thek’s career, Relativity Clock, is currently on view at Alexander and Bonin, New York, through October 16, 2021.